ELI5: All about balance sheets and how to make them suck less, Part 1

Editor’s note: This series is for people who are not CPAs, bookkeepers, CPFAs or any other kind of finance professional. Instead, it’s for the harried business owner who has about 20 minutes a week to look at Quickbooks and decipher what the hell is happening, why it matters, and what to do with it.

This is Part 1 of a two-part series. You can read Part 2 here.

Kill. the. balance. sheet.

Just saying those two little satan-beloved words — balance sheet — to a business owner makes most of us remember that we’re supposed to be getting a root canal right now. We hate balance sheets more than the Red Sox hate the Yankees. More than Indiana Jones hates snakes. In fact, you might get a better reaction if you replace “balance sheet” with “tortured to death by spiders with tiny knives.”

As much as we’d all like to throw them into a fire with a solid lifetime hex, however, the balance sheet is critical to understanding the condition of a business.

Need an example?

It’s possible to have a lot of money in the bank and still be on the edge of bankruptcy. Imagine getting a huge bonus so you take the whole family to Disney, but in your googly eyed state over a huge bank balance you completely forgot that you just put a new roof on the house and the loan repayments start next month.

Definitely not a Happiest Place on Earth kind of feeling.

Balance sheet 101

Okay, so…what in the actual hellfire is this thing?

We’ve already been through the ins and outs of a profit-and-loss statement. Understanding that can be a difficult concept, but ultimately straightforward — money comes in, money goes out. There’s either a profit or a loss.

So why do we need a balance sheet at all?

Because we want the profit and loss statement (P&L) to give us accurate information. Without a balance sheet, the P&L will lie to us, as we will see in examples shortly. Without a balance sheet, you’d have no idea how much profit — or loss — you actually had.

Weird, right?

Let me explain.

The balance sheet does something very simple: It tells you how much money you have left in your accounts — your balances, as it were. It works equally well for bank accounts and cash drawers. It also tells you how much of your money is owed to other people’s accounts.

To illustrate this in practice, we’re going to once again return to a much-loved HTB.com example business: a hot dog stand. If you own this business and have a loan, for example, the balance sheet tells you how much you owe. It also lists your unpaid bills, like how much you still owe to your hot-dog supplier for the hot dogs you bought last week but haven’t paid for yet.

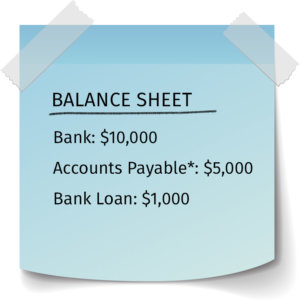

Here’s a simplified example of what a balance sheet might look like:

This means you have $10,000 in cash in your bank, but you owe other companies $5,000, and you owe your bank $1,000 on your loan.

*Accounts Payable is a fancy way of saying “How many bills do you have from vendors that you haven’t paid yet? If you have an internet bill from Comcast that you haven’t paid yet, for example, the amount goes into this bucket.

Simple start, right?

Next: Assets and Liabilities

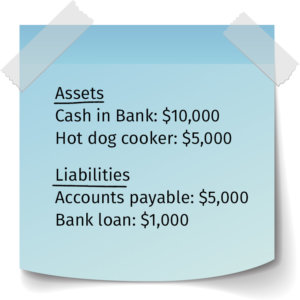

Time to complicate things. The next step is to look at two additional items: assets and liabilities. An asset is real money (cash) or potential money (unpaid invoices) that you have. A liability is money that you owe other people, like a loan or a bill.

Remember the part about a balance sheet being critical for your P&L? Here’s how it all ties in.

Imagine your P&L looks like this:

Looks good! I sold $1,000 worth of hot dogs and made $150 in profit. But what if I bought a new hot dog cooker this month? That changes things:

Well, fudge. That’s not even close to the $150 profit I thought I had. In fact, I lost $4,850 on $1,000 in sales. That’s a net profit margin of -485% I should clearly give up on business ownership and go back to working for The Man. Except that isn’t true, either.

I didn’t really lose $4,850. I chose to spend $5,000 buying a new cooker. To set the story straight, you use — you guessed it.

A balance sheet.

Instead of saying we spent $5,000 on the cooker in January, we put that $5,000 on the balance sheet as an asset. Because it’s just a bank account in the form of a hot dog machine. We could take it to a pawn shop and get money for it tomorrow — it’s money in a physical form.

Here’s what it looks like with that adjustment:

Okay, we’re getting somewhere. However, the hot dog cooker isn’t free. We spent $5,000 on it. That does impact the P&L, but the question is for how long?

In Part 2, learn about how depreciation throws another piece into this puzzle and what you can do to try and keep track of it all.

As much as we’d all like to throw them into a fire … your balance sheet is critical to understanding the condition of your business.