ELI5: Balance sheets and how to make them suck less, Part 2

Editor’s note: This series is for people who are not CPAs, bookkeepers, CPFAs or any other kind of finance professional. Instead, it’s for the harried business owner who has about 20 minutes a week to look at Quickbooks and decipher what the hell is happening, why it matters, and what to do with it.

This is Part 2 of a two-part series. You can read Part 1 here.

In Part 1, we took a look at how profit-and-loss (P&L), assets, and liabilities can affect a balance sheet. We’ll pick up Part 2 here with an even more convoluted and crazy-making addition: depreciation.

To recap: In this scenario, you’re the owner of a hot dog stand who’s trying to understand the ins and outs of your balance sheet. You need to know what it is, how it can help you from accidentally going into the red, and which numbers actually matter. So far we’ve covered the basics, along with assets and liabilities.

Up Next: Depreciation

In Part 1, you bought a new hot dog cooker for your stand. Let’s assume that hot dog cooker cost $5,000 and will last for eight years. It’s great that you’ll have it that long, but it won’t be worth that much when it finally clunks out — that’s where depreciation happens! To calculate the loss of value over time, we take $5,000, divide it by eight years, and we see that we’re really spending $52/month on the hot dog cooker. Here’s how that looks on our P&L:

Ta-da! With a little of the magic commonly known as math, you have a much more realistic profit-and-loss statement. The example above is an honest look at how your business is doing. The problem is, you spent $5,000 on it, not $52. So where does the other $4,948 show up? It goes to the balance sheet!

And what’s the word that describes this relationship between the P&L and the balance sheet? Depreciation. A word so ugly its mother smacked the doctor when it came out. Luckily, it’s less complicated to understand than to pronounce (it’s “appreciation” but with a dee at the front instead of an uh).

It’s like this. Think about a bank account. In a bank account, $1,000 is always worth $1,000. Your hot dog cooker, however, loses value every month. It started at $5,000, with depreciation being the concept that you “use” $52 worth of it every single month. Noting that $52 loss of value on your monthly balance sheet reminds you that it’s not worth the full amount you paid for it.

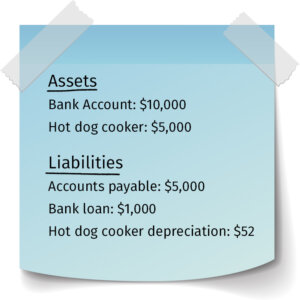

Here’s what it looks like on a balance sheet:

Is adding a whole new line to the balance sheet the single most complicated way to do this? Yes. Is there a good reason for it? Also yes.

The original price is kept in the asset section simply so that you know how much you originally paid for stuff. And if you own a bunch of stuff — cars, machinery, buildings, etc. — it’s important to know the original value for several reasons:

- It reminds you what you paid for something. This comes up a lot, and our memories are easily wrong, so having an at-a-glance reminder of “How much was that car?” or “How much was that buildout?” helps you figure out what to expect next time.

- It helps with strategic planning by telling you how much useful life that thing has left. If you have $5,000 in assets and $1,000 in depreciation, that equals $4,000 in depreciation value left for your taxes in the future. You can also estimate that you’ve used up about 20% of the useful life of that piece of equipment. This matters a lot if you open a brand-new store with lots of brand-new equipment. Knowing roughly how long it is until you probably have to replace it can be the difference between “saving enough” and “Oops, we can’t afford a new hot dog cooker because we also need a new fridge and a new cash register at the same time.”

- It can be moderately helpful if you ever decide to resell a piece of equipment, as long as your numbers reflect the reality of its actual value. (Because that’s not often the case, however, you’ll still have to “math” a little bit to calculate its value.)

So, depreciation is useful. And at its most basic, it says “You’ve used up this much of the thing you bought.”

That said, figuring out how much of the thing has been used up — that’s work for your CPA. What makes the balance sheet a little less useful is you don’t get to determine by yourself how long the useful life of each thing you buy is. The IRS rules for determining the useful life of stuff are complicated, and it’s better for your mental health to let someone else learn them. As long as you understand the basics — depreciation is how much of the useful life of an object you’ve used up — you’re good. The IRS rules are usually reasonable and close to reality, but they’re often not exactly right.

Next: Amortization (sorry)

Such an icky word, isn’t it? And it’s one that most people hear but have no clue what it means, beyond being some sort of word banks use when talking about loans. The good news is: You already know what it means. Amortization is exactly the same as depreciation, except it refers to intangible, non-physical stuff.

For example, you would depreciate a car but amortize the value of a patent. Computer equipment? Depreciation. Loans? Amortization. It’s the exact same concept of reducing the value of something by a set amount, but different based on whether you can touch the actual thing or not.

Last But Not Least: Equity

We’ve covered assets, liabilities, depreciation, and amortization. That’s a lot. You’re well on the way to becoming a balance-sheet rock star, but there’s just one more thing.

Equity.

It’s an easy one, and it even has its own equation:

assets – liabilities = equity

Equity is extremely important because it’s the bottom line — the net worth of your business. If you take all the stuff you own (bank accounts, cars, unpaid invoices) and subtract all the stuff you owe others, as well as the decreased value of your stuff (depreciation, bills you need to pay, loans), you have the liquidation value of your company.

And that seems like a useful number to know, yeah?

P.S.

If your brain already hurts, this information is just nice to know. But if you want a little more, I’d like to offer you some perspective on why the balance sheet isn’t always an easy way to get the true story.

Would you like some tea?

The reason balance sheets are so complicated is that a lot of people used them to cheat on their taxes. As a hypothetical, AnyCompany would avoid paying taxes on a $5,000 profit by randomly depreciating a $10,000 piece of equipment by half. $5,000 in depreciation brings the profit down to $0, and you can’t tax nothing.

As a result, the IRS put complicated rules in place to prevent that. If a company has a car, for example, they don’t get to decide if it will last three years or 15. (Some people trade in every couple of years, and others drive their cars until the wheels fall off, then duct-tape them back on and keep going.) Regardless of those personal decisions, however, the IRS dictates depreciation.

For cars, it’s five years. No more, no less.

That’s a relatively short timeframe to get to a place where a car is showing as “zero” value on your balance sheet, but you may still be using it and it may still hold obvious value to you. Those are just things we deal with when we read our balance sheets and factor into how we tell the story. On the bright side(?) though, companies can no longer eliminate a $5,000 profit by just deciding their company car lost $5,000 in value this year.

Why this all matters: A personal perspective

Not understanding the importance of balance sheets is how I almost went bankrupt, despite having a lot of money in the bank. I was paying all the attention to my bank balance, but I didn’t understand — or care to understand — my balance sheet.

It went like this:

I made a big sale! I sold $90,000 worth of computers and I got paid right away. Happily, I had Net 30 terms with Dell, so I was able to deliver the computers to the customer, put $90,000 in the bank, and not worry about paying Dell for 30 days. I sold at a good profit margin, so I only owed Dell about $40k. Hurray, I had $50k to spend!

Except I lost track. I spent way more than the $50k and didn’t pay attention to what I owed Dell. Until day 31, when Dell called me demanding payment, and I only had $30k left to pay their $40k invoice.

I had to scramble to come up with the remaining money. (Ever called a customer *begging* to get paid *right now?* I have.)

If I’d paid attention to my balance sheet, I would’ve seen that and avoided the panic attack that comes when you realize that what you have coming in is less than what needs to go out.

TL;DR

That was a lot. Since balance sheets aren’t one those intuitive things that you can learn via osmosis, here’s a quick recap of both articles in this series:

What it is

A balance sheet is a document that helps you track the cash coming in and out of your business. It includes things like assets, liabilities, depreciation, amortization, equity, accounts payable, accounts receivable — basically, everything to do with your business that involves a dollar amount.

What it does

Because it takes so many factors into account, the balance sheet gives you a complete (if complicated) picture of the actual financial health of your business. It shows you the truth about your cash-flow situation, how much the items you’ve purchased are still worth, and where you are in the journey to paying off your debts.

Why it matters

Knowing the health of your business is vitally important, for obvious reasons. But you aren’t the only person who needs to know this information. If your business meets certain requirements, Uncle Sam is going to need you to fill out Form 1120-S, which includes a balance sheet (Schedule L). Investors and analysts also pay close attention to balance sheets to determine whether to invest in a company.

What I’m saying is, it’s a thing you have to do. But the work is worth the reward.

Related content:

Balance Sheets, Part 1

Profit: One Bottom line, a Bunch of Ways to Get There

Depreciation is complicated