Manager Series, Part 2: How to Write an Employee Performance Review

This is Part 2 of a 7-part series on management best practices, tips and tricks, and what not to do.

Part 1 starts with the basics of being in management, and how to be a good manager.

Part 3 covers getting good job performance from your employees.

Part 4 gives you ways to manage difficult employee conversations.

Part 5 helps you decide whether it’s time to fire someone.

Part 6 shows you how to fire someone properly.

Part 7 talks about how to tell the remaining members of your team that someone has been fired.

Congratulations, you’re a manager! Maybe this is your first day, or maybe you’ve been doing it for a while now and have figured out that being in charge of other humans isn’t for the faint of heart. (Don’t worry, your secret is safe with us.) No matter how you got the title, though, and no matter how many people you’re managing, your path to either beloved or bemoaned starts in the same way — you have to figure out the qualities, pro and con, of those working on your team.

It’s not something managers receive a lot of training on, but understanding how to evaluate your employees is one of the most important parts of a manager’s job description. It will profoundly affect your relationship with your employees.

Without proper training, here are some of the most common ways managers judge their employees (relevance, effectiveness, or general decency notwithstanding):

- The level of effort they appear to put into their jobs. This means looking at things like how stressed out they seem or how much they talk about how hard they’re working. Level of effort (LOE) is also commonly judged by the messiness of a person’s work area.

- The extent to which they look like you and like the rest of the team. Like these somewhat eerily similar teams. The more an employee looks like the rest of you, the better fit they’re likely to be. The less they look like you, the worse they’ll be in their jobs.

- How committed they are to the company and its mission. They can recite the core values by heart, post online about how #blessed they are to work for the company, or get a company logo tattoo during a corporate retreat.

Here is the nice thing about these rating systems: They’re easy, and they make a new manager feel smart because they already have the required toolsets to use them — all they need are eyeballs and opinions.

But you probably knew before we started that it wouldn’t be that easy.

Evaluating employees is a new and difficult skill, but we’ve put together a step-by-step guide to do it effectively, fairly, and with aplomb.

Step 1: Write a List of the Important Behaviors

Don’t you wish you had a nickel for every time you’ve heard someone described as a “good” or “bad” employee? It’s a common categorization, but in reality there’s no such thing … as either. Every employee exists somewhere between “Does the Thing I Want Perfectly Every Time” and “Never Does the Thing I Want, Ever.” No one sits on either of those extremes, because even the most gung-ho company ambassador has an off day once in a while.

The key to ditching these stereotypes is to find the sweet spot on that spectrum, and you do that by figuring out the behaviors you want your employees to use, as well as those you’d prefer they suppress. When you do this, the role of the manager becomes clear: Promote and reward the behaviors you want; remediate to decrease the ones you don’t.

It’s easy in theory, but outlining those behaviors can be a bit trickier. Behavior by definition is something we can see another person doing with our eyes. That may sound facile, but it’s an essential concept. Why? Because when managers aren’t clearly directed to focus on employee behaviors, they tend to focus instead on their thoughts.

There’s a real danger there, because even though some managers may have empathy in overdrive, they still aren’t mind-readers. And the more time a manager spends wondering if their employees really care, or what they really think about the company (or them), it can lead them to some incorrect conclusions.

A behavior, though, doesn’t require psychic ability. You can see if an employee is doing a task correctly, if they’re not following the rules, checked out, or if they’re doing the things their job requires of them. All that said, here’s what a list of behaviors might look like:

- Retrieves mail and deposit checks daily

- Responds to emails from vendors within 48 hours of receipt

- Assists CPA with gathering information for filing tax returns

- Reconciles employee expense reports against their credit cards monthly

What all of these things have in common is that you can see them and measure them in the real world. “Meets deadlines” is something you can measure. “Believes in the company’s mission to succeed” is not. (That is, of course, unless you work at a place like Walmart, where employees are required to shout the company chant at the start of every shift. Participating is something that can be measured … whether it should be is debatable.)

In other words, an employee can be damn good at their job, whether or not they give a fig about the big picture. On the other hand, though, they might be a huge fan of the mission but suck at their jobs.

Step 2: Put Theory Into Practice

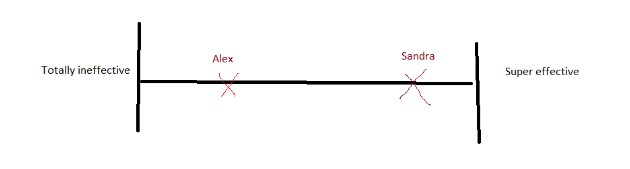

When it’s time to evaluate your employees, you’ll look at them not as “good” or “bad,” but on a spectrum of effectiveness against their expected behaviors. For a visual aid, draw a line for each person with “totally ineffective” at one end, “super effective” at the other, and whatever in-between stages you prefer. This will give you a clear picture of where your employees stand, as well as where their strengths and weaknesses lie. (This is especially helpful if you’ve taken on a new employee or a new team.)

Keep in mind that effectiveness can only be judged in its relativity to the person’s job description. For example, you can’t fairly call Alex “totally ineffective” as a PowerPoint designer if his job is plumber.

Another thing to write down on a sticky note is that roles are occupied by people and not the other way around. If you need someone to do the accounting behaviors, you need a human, and let’s say that person’s name is Jackie. When managers begin to see people as roles it can become difficult to evaluate them as the humans they actually are.

If Jackie is accounting, for example, then whatever Jackie does must be right for accounting, because she IS accounting. If Jackie occupies the role of accountant, on the other hand, she can be evaluated against what is expected from the role and take it from there.

The Bottom Line

When you know how to define the relevant behaviors for each role you’re managing, you’ll find it far easier to understand how effective or ineffective each employee is against those behaviors. And you’ll never fall into the trap of evaluating an employee for what they believe (or what you think they believe).

Next up: How to sit down with your employees and have that conversation about their behaviors.

Related content:

Manager Series, Part 1: What No One Ever Told You About Being a Manager

Manager Series, Part 3: How to Get Your Employees to Give You What You Need

Manager Series, Part 4: Techniques for Managing Challenging Conversations

Manager Series, Part 5: Reasons to Fire an Employee

Manager Series, Part 6: How to Fire Someone

Manager Series, Part 7: Telling Your Team Someone Was Fired

“Meets deadlines” is something you can measure. “Believes in the company’s mission to succeed” is not.